“Flow” winning an Oscar for Best Animated Film has been celebrated — specifically by us here at IndieWire — for its use of the free-to-download software Blender, which enabled the film’s Latvian animation team to craft a lush, human-free world of staggering beauty and rising water.

Practically at the other end of the spectrum of what’s possible, director Julian Glander has created a lo-fi, distanced, painfully, poignantly pastel vision of Florida in “Boys Go to Jupiter.” The film was also made in Blender, but this vaporwave coming-of-age story couldn’t look or feel more different.

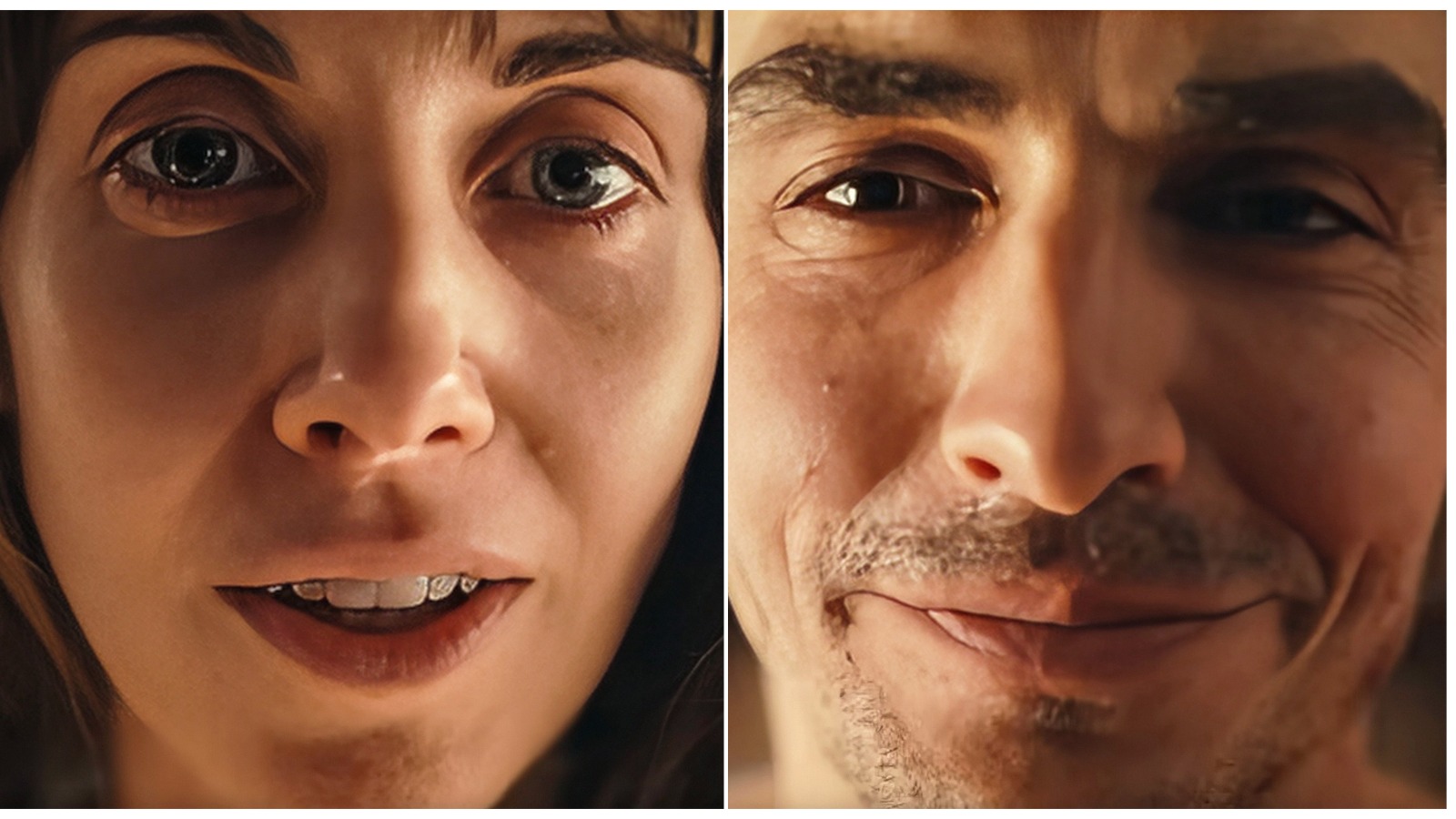

The story follows intrepid (and intensely sleep-deprived) teenaged deliverista Billy 5000 (Jack Corbett) as he tries to hustle for the $5,000 he hopes will give him the independence he craves, even as absurd and miraculous things keep happening around him, his friends, and an orange juice factory run by Janeane Garofalo and Julio Torres. In the exclusive clip above, you can watch Billy’s long walk home, over a musical interlude and the equally transporting landscape of the Florida highways, after his phone and his trusty swagway die.

IndieWire spoke to Glander about creating the feature on a regular MacBook and how the look of the film was influenced both by the timeless alienation of being a teenager and this specific moment of Internet enshittification, why Florida is the Petri dish of America, and how independent films can find surprising, rewarding ways to make financial or logistical constraints work for the stories they want to tell.

The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and length.

IndieWire: As someone from Louisiana, I really appreciate the oppressively hot winter vibes going on in the film. There’s this humid weirdness you’re able to capture through the animation style.

Julian Glander: I’m glad to hear you say that. It’s definitely the same region and has some of the same weirdness. I actually don’t know Louisiana very well, but for the purpose of your enjoyment of the film, let’s say it’s the same thing.

Oh, I mean, it doesn’t have to be. The aliens are in Florida. That makes sense to me.

Yeah, it does make a lot of sense. I feel as if we all understand Florida as America’s hell. It’s like the Petri dish where America kind of happens. I kind of think of it as all coming out of Disney World — the invention and the construction of Disney World 75 years ago, the conquering of the swamps, and then the sort of decay of that whole magical fantasy is the world where this movie takes place.

It looks like it was made in Blender. Is that how you created this world?

This was made in Blender.

Hell, yeah. We love anything anyone can download for free to make art.

Well, this is the radical promise of the Internet. We love Blender — the software of the year, the hot software of the moment. I think about 20 years ago, when I was on AOL Kids, [there was] this idea that all these tools would come to us and all this amazing creative expression would happen, and I certainly started my career during what I think of as a golden age of that on Tumblr. We’ve almost seen a constriction of it and a re-platforming and a reorganizing of the Internet that’s very unsatisfying. I think you’d be very hard-pressed to find someone in 2025 who’s like, “I enjoy going online. I like the Internet.” And that wasn’t the case 10 years ago.

Being someone who went on the computer all day was, for a moment, almost something to be proud of. That’s also something the movie is talking about: The way we’ve all been kind of hoodwinked by the gamification and by the pastel fantasies the tech industry sold us, and the way that they restructured our entire lives — in some ways without our permission, and in some ways with our completely willing buy-in.

I wrestle with this all the time, where it’s like, “Am I just getting older? If I were a teenager now, would I still be experiencing exciting connections online?” Probably. But that’s also something I want to talk about in the movie. Part of being a teenager is finding a way to have a beautiful life or see the beauty in the world when you basically have no good options.

Can you talk a little bit about character design for your teens and others? I’m curious if you experimented with the scale of the world or the level of expressiveness on the characters, and how you finessed all your weird little guys.

I’ve been doing 3D illustration for about a decade now, and a lot of the visual language has developed from the constraints of Blender — specifically the constraints of using Blender, which is infinitely powerful, on my tiny little computer. I just have a MacBook. But I would say part of the look of the movie comes from Florida. I grew up there. I haven’t been back in a long time, so this is how I remember it: This very dreamy, sun-drenched, acid pastel place with a little bit of gunk on it.

The other part of it is this idea of the gamified world, where we see these characters a lot through the isometric point of view and from some distance. That is a very economically efficient way to make scenes and make a movie. It avoids some of the most expensive stuff in 3D animation, which is camera movement and character movement — specifically moving around within scenes. But I also think, creatively, the sell there is that we’re looking at characters who have been isolated from each other and dehumanized in a way because of this new way of working that has been foisted upon us over the last decade.

It’s this really lovely blend of the logistical and economic realities and creating characters that fit those constraints and a story that really thrives off of them, actually.

That’s the story of independent filmmaking. To me, it feels like we’re at the same moment live-action films had 15 years ago, when all of a sudden everyone had iPhones and everyone started being born with some camera literacy. I think the same thing is happening in animation now. The tools are definitely there — and beyond the tools, the educational resources are there and the communities are there.

We had to find every shortcut there was, and then we also had to find a way to make that work creatively. Like, almost nobody walks in the movie, because walk cycles in animation are very time-intensive and when they look wrong, you can really tell. It just shatters everything. So we have characters standing behind gates, characters on wheels a lot or behind doors. Billy, our main character, is on a swagway for most of the movie because it’s the easiest thing to animate, but also, I think, sells his character as an aimless young man who’s floating through life in a very ghostly way, trying to be unobserved and unnoticed.

The swagway is so key to him. Can you talk about the scene where he actually has to walk home in the dark after his phone and his swagway die? That also has a great song, in that moment, too.

I really like that scene because it takes place at night, and so we get to see everything we just saw in a different light, and it’s new again. The thinking there was, “OK, Billy has to move through town, and this is the moment where we can show how small he is by putting him up against his actual surroundings.”

This is something people talk about a lot in urban development — when you live in car-centric America, the scale of everything is off. It’s not done at human scale. I think Billy’s point of view in that scene is like he’s in a world that’s too big for him; and the billboards that he walks past — I think one of this is for the lottery, one of them is saying you’re gonna die and go to hell, and that just sort of hangs over the movie.

That’s a scene that kind of bridges Day 1 of the movie into the next day, where his life really starts changing. Like in a traditional musical, I guess that would be the end of the first act song. This is the stasis. This is how things are. But let’s see what’s going to happen next.

“Boys Go to Jupiter” will be released on Friday, August 8 by Cartuna and Irony Point.