“The 1970s for those of you who missed them were a fabulous time to be young and brave…[Life] and what to make of it was up for grabs. And there was a tremendous feeling that all was new and beautiful if you had the nerve to make it so… The opposition to [the Vietnam War] had given an entire generation the will to break the rules. Our President, Nixon, had quit one step ahead of a prison term. One can always hope that might happen today.”— “Slap Shot” screenwriter Nancy Dowd, 2006.

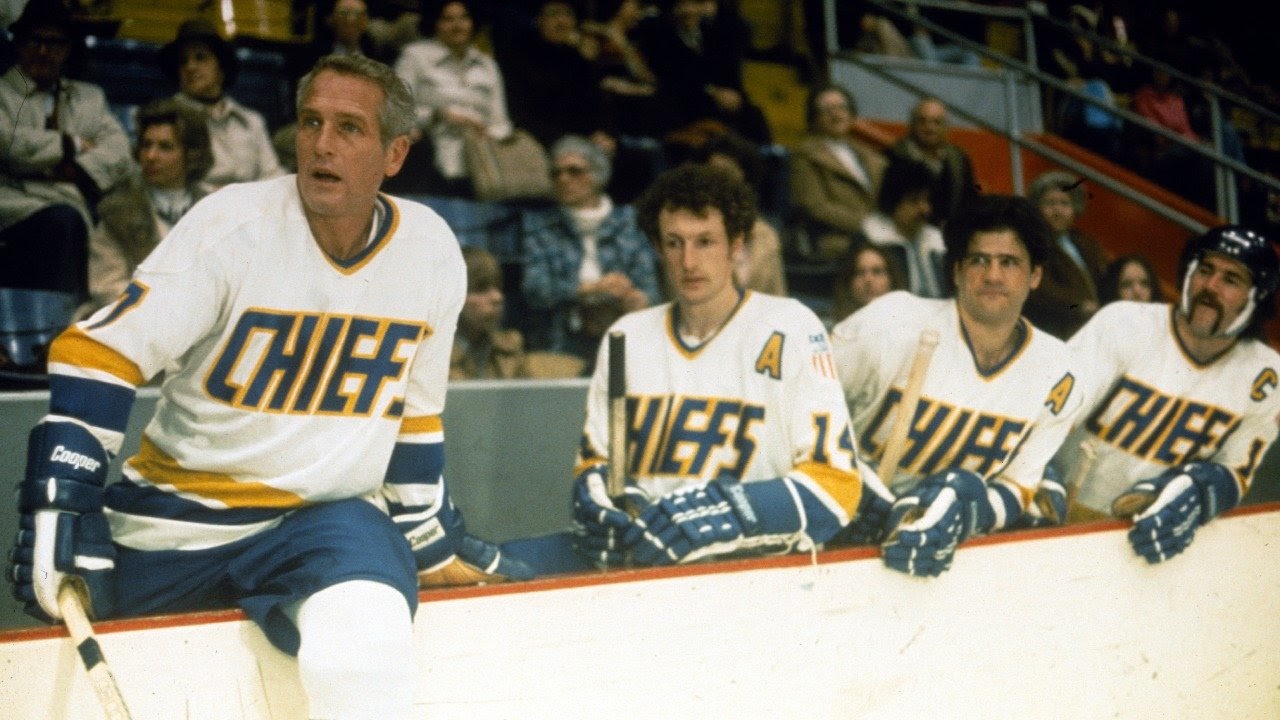

Reggie Dunlop (Paul Newman) never received the memo that everything folds eventually. Or maybe he just refused to read it. The player-coach for perennial losers the Charlestown Chiefs, the minor-league hockey team in fictional factory town Charlestown, Pennsylvania, he can’t accept that he’s getting older and won’t be able to lace up his skates for much longer. Just like he can’t accept that his beloved team stinks so badly their few remaining fans show up to games only to jeer them, or that the Chiefs are on the chopping block once the local steel mill shutters and 10,000 workers go on waivers.

“I was thinking about you the other day, tryin’ to imagine you when you’re through with hockey, and I couldn’t,” his estranged wife Francine (Jennifer Warren) gently tells him after the millionth failed attempt to reconcile with her. “There was nobody there,” she says with haunting finality, because Reggie and minor-league hockey are functionally synonymous. When she asks what he’s going to do when the Chiefs eventually go under, Reggie cheekily responds, “I’m gonna come back to you!” because he also can’t accept that their marriage is over.

Reggie’s resolve to fight against the rising tide inspires him to embark upon a harebrained scheme that involves con artistry and theatrical promotion. To fulfill the bloodlust of the Charlestown crowd, who enjoy watching players fight during games (possibly to vent their economic frustration), he unleashes the Hanson Brothers on the ice. The three childlike siblings, who all wear thick black-rimmed Coke-bottled glasses and often speak in cartoonish unison, were previously a cost-saving embarrassment for the Chiefs, but their penchant for brawling and immature antics quickly garner the team popularity as ruthless heels. As ticket sales skyrocket, Reggie manipulates the local media into talking up a fabricated story about a potential sale to Florida to motivate the players even more and hopefully generate real interest in the team.

Newman plays Reggie with a permanently mischievous glint in his eye and a schemer’s grin. By the late 1970s, the renowned American actor had become a member of the old guard, and yet he retained the boyish charm that propelled him to fame playing anti-authoritarian rebels and grifters in films like “The Hustler,” “Cool Hand Luke,” and “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.” Newman’s ingrained impish defiance combined with his salt-and-pepper good looks lends Reggie the perfect avatar for the reckless, anarchic tenacity that defines George Roy Hill’s cult comedy, a movie about self-destruction in the name of existential survival.

As long as there’s an NHL and recreational hockey endures as sport, “Slap Shot” will have its place as a locker room classic. The film not only understands the sport in its bones, but its combination of gleefully vicious violence and slobs-over-snobs goofiness can still energize any testosterone-filled group. At the same time, the proud vulgarity that courses through the movie feels like slight misdirection, a way to keep people in their seats while giving them another slightly more sophisticated narrative about privilege and power, deindustrialization and imbalanced labor relations, and a determination to be free even if you still have to serve somebody.

“Slap Shot” is funny and profane, one of the all-time great bad-taste comedies of any era, but its canny, sensitive screenwriter Nancy Dowd had more on her mind than one might expect from a film that features Paul Newman taunting a rival player about how his wife “sucks pussy.” She infused the screenplay with rhetorical realism — the verbal texture of life lived amongst snarky grinders — and palpable nonconformist yearning, both of which stem from her own experience with family rebellion. Dowd acutely understood the experience of bucking expectations and giving the middle finger to anyone who tells you to fall in line.

***

Dowd wasn’t supposed to be writing the screenplay for a movie like “Slap Shot.” The daughter of a wealthy machine-tool plant operator from a General Motors factory town, she was supposed to become a respectable member of society, fulfilling the destiny of “an ever upward American trajectory” established by her family’s noble immigrant pedigree. Instead, per her own words, “the rocket veered off course.” According to her father, Nancy was looking “like a railroad worker in jeans and a blue work shirt” instead of a candidate for marriage. Meanwhile, her college-educated brother Ned had turned away from the family business to start playing for a losing minor-league hockey team in a two-bit town.

Ned’s experiences with the Johnstown Jets, based in the eponymous Pennsylvania mill town, shaped the core of “Slap Shot.” Minor-league hockey in the ‘70s was a notoriously brutal sport: The potential for violence at games was often a primary selling point, and players often leaned into the expectation for clashes on the ice. (Reg’s wrestling-like ploy to boost profits by feeding off the public’s bloodthirst isn’t too far off from reality.) Nancy admitted to being fascinated by the fighting stories her brother would relay to him over the phone, and in the eventual script she incorporated many anecdotes of outrageous skirmishes, many of which involved Jack, Steve, and Jeff Carlson, the real-life inspiration for the Hanson Brothers.

But it was when Ned drunkenly called up his sister in the wee hours of the morning to inform her that the Jets were either folding or being sold that Nancy set out to write the film in earnest. In particular, it was Ned’s ignorance regarding the Jets’ owners that galled his sister. “It was incredible to me that my brother did not know who owned his team,” she once remembered. “If you didn’t know who owned you, what did you know?” Nancy channeled that mystery into “Slap Shot” as Reggie struggles to determine who actually holds the purse strings in order to properly appeal to their pecuniary interests.

Nancy had plenty of reasons to want to control her destiny. A second-wave feminist who grew up around enough bored suburban housewives to last a lifetime, she was determined not to be stuck at home raising children and cooking for a husband. Instead, she attended Smith College and studied abroad at the Sarbonne where she spent much of her time at the Cinémathèque Française. She later enrolled in the UCLA film program for a more formal education and worked as a student assistant under King Vidor. She befriended prominent figures like Jane Fonda, who asked her to collaborate on the anti-war documentary “F.T.A.” and eventually commissioned her to write the screenplay for Hal Ashby’s “Coming Home.” “I refused to be a 1950s zombie,” she insisted.

Nancy beautifully filters her own privileged background into “Slap Shot” through top-scorer Ned Braden (Michael Ontkean, who actually played Division I hockey) and his wife Lily (Lindsay Crouse). Both college graduates who could land well-paying jobs through their families just like the Dowds, they insead followed their bliss right up until it made them depressed. A stubborn idealist, Ned despises Reggie’s carnival-barking tactics and prefers to lose clean than win dirty. He takes out his frustrations with the Chiefs on Lily by treating her with unconscionable coldness when he’s not philandering around town. Meanwhile, Lily descends into acerbic alcoholism; she hates minor-league culture, the one-note wives she’s expected to pal around with, but mostly she hates herself for putting up with it all.

“It’s ridiculous for us to be here,” Lily sneers to Ned at one point. “We stick out like a couple of sore thumbs.” She might be right, but Dowd’s script emphasizes the ridiculousness of their entire environment. Victor Kemper’s grimy photography accentuates the depressed environment of a steel town corroded by economic stagnation, yet it exists in productive tension with George Roy Hill’s wide comic framing, which captures the absurdity of literally trying to fist fight despair. As the Hanson Brothers become borderline-criminalistic folk heroes and Reggie does everything to goose up excitement including calling for a bounty on a rival player’s head to boost on the radio, the Chiefs devolve into a crew of “actors and punks” rather than genuine athletes. All the while the public and the media eat it up seemingly because there’s nothing else to root for.

It’s only when Reggie finally meets owner Anita McCambridge (Kathryn Walker), the supercilious woman who holds the purse strings, that he realizes his soul-selling approach was for naught. Though she could probably sell the team for a decent amount, she would make more profit if she folded the team as a tax write-off. “We’re human beings, you know?” Reggie mutters pathetically, but what Dowd’s script acutely understands that anyone with authority over them — from their penny-pinching manager to the fans whose loyalty heavily depends on either the Chiefs record or their entertainment value — sees them as nothing more than cattle. Just like the mill turned its back on their workers, Anita cares about her bottom line infinitely more than whether the Chiefs’ players go hungry. It’s always been every sucker for himself.

***

American institutions have always been less sturdy than we were led to believe, and they’re eager to abandon individuals the second they stop being useful. Societal neglect will inevitably breed a coarseness in manner and language, exhibited by the uncouth nature of the Chiefs’ players as well as the public watching them. “Slap Shot” garnered quite a bit of notoriety upon release for its profanity, particularly because it was written by a woman. Vincent Canby of “The New York Times” described Dowd as “a young woman who appears to know more about the content and rhythm of locker room talk than most men,” while Frank Rich of “The New York Post” remarked that she “has an ear for American vernacular that even Ring Lardner might have appreciated; she realizes that cussing can be an exhilarating folk art.”

Dowd spent a month with her brother’s team as research and worked from tape recordings sent by Ned and his teammates to craft the dialogue in her slice-of-life screenplay. (In fact, Ned alongside many of his fellow players appear in the film in roles big and small.) “I used the exact language that the players did,” she said in an interview upon the film’s release and scoffed at the rumor that her name was a pseudonym for a man. “The world has a weird view of women,” she argues. “People seem to believe that we have to write about divorce or suicide or children…But we’ve been around. Women aren’t sequestered anymore.”

She similarly bristled at the accusations of sexism leveraged against the film, given her feminist bona fides. The boys in “Slap Shot” might look like they have all the fun, but it’s at the obvious expense of their brains and bodies. Meanwhile, the most perceptive characters are the women: despite her self-destructive behavior, Lily is hardly naïve about her choices in life or men. Francine knows enough about Reggie’s loopy charm that it’s bad news in the long run and leaves him for good even if he still holds out hope she’ll come back to him. Even Anita, the closest figure the film has to a villain, is merely playing the capitalist game just as well as her hypothetical male counterpart.

Unlike the profanity in “Slap Shot,” which now keeps pace with a world that becomes cruder by the minute, its homophobic language stands out as the film’s real obscenity to contemporary ears. It goes without saying that certain slurs and accusations were unfortunately part and parcel with the hyper-masculine milieu of the era. Sometimes it’s funny, like when Reggie, after being accused of sucking cock, says with a smile, “It’s all I can get!” Other times, it can leave an unproductively sour taste, like when Reggie antagonizes Anita on his way out the door by insinuating her young son “looks like a fag” who will “have somebody’s cock in his mouth” unless she gets married again.

At the same time, however, the fragile masculinity neatly dovetails with the numerous ironies and contradictions that course through the film. The recurring motif on the soundtrack for a film populated by hotheaded, hyper-masculine athletes is Maxine Nightingale’s disco hit “Right Back Where We Started From.” Despite hailing from money, Ned and Lily are angrier and more depressed than any of the near poverty-stricken players with whom they hang around. One minute, Reggie will espouse progressive views when he’s in bed with a rival player’s ex-wife who has recently started sleeping with women by claiming that “women’s bodies are beautiful”; in the next, he will gleefully rattle that player during by taunting him about his wife’s sexuality.

But it all comes to a head in the film’s climactic scene, which throws the social hypocrisy inherent in the environment into sharp relief. After pledging to play a clean game for their last hurrah, the Chiefs get physically pummeled by the opposing team, who deliberately packed their lineup with vicious goons, during the first period; after learning that NHL scouts are in the audience, the team immediately reverts back to their violent ways. But upon seeing Lily in the stands, made over by Francine and cheering on the Chiefs, Ned decides to subvert the aggression by performing an elaborate striptease on the ice in a public display to woo his wife back.

“I don’t want any youngsters to get the idea that this is the way to play hockey!” exclaims the announcer, who was previously salivating at the chaotic bloodshed that occurred minutes prior. The rival player coach decries Ned’s perversion and demands the referee put a stop to his behavior. Ned views the team’s evolution from old-fashioned fundamentals to sideshow exploits as an existential threat rather than an enterprising venture because he’s innately someone who “don’t run with the traffic,” per Reggie. In the last game however, he joins the circus on his own terms and weaponizes the opposition’s gay panic to the point of them forfeiting the game. Dowd’s script stresses an obvious, potent takeaway: Violence might be socially acceptable, but public erotic displays, especially ones aimed at women, are obscene.

Dowd never again worked on a film without serious complications. Her original script for “Coming Home” was radically reshaped by multiple writers and personalities and publicly decried the revised version as “terrible” before the film even came out. (However, she still retained a “Story by” credit on the film and subsequently shared an Oscar for Best Screenplay.) Dowd walked off the set of “Ladies and Gentlemen, The Fabulous Stains,” a proto-riot grrl teen musical drama, after clashing with director Lou Adler on the ending and being groped by a camera operator; she ultimately took her name off the film and used the pseudonym “Rob Morton.” She used that same alias once again after Warner Bros. drastically recut the film “Swing Shift” against the wishes of her and director Jonathan Demme. Dowd’s resumé is subsequently littered with pseudonymous credits and uncredited contributions on acclaimed films like “Straight Time,” “North Dallas Forty,” and “Ordinary People.”

Dowd’s commitment to uncompromising work within a business so indifferent to the value creative integrity likely pushed her out of Hollywood. But her righteous, empathetic voice still rings out in a film about people desperate to live on their own terms within a society so committed to capital they’re willing to squeeze out every ounce of beautiful, ugly humanity from the world. Her desire to be free, her abject refusal to “to stumble around in the darkness and waste my precious life,” into Reggie Dunlop, a man so determined never to work a bullshit nine-to-five job that he would put his body at risk to continue skating with his fellow tainted angels. Nancy Dowd, like Like M. Emmet Walsh’s sports writer Dickie Dunn, merely “tried to capture the spirit of the thing” with “Slap Shot.” Only the “thing” in question was the American character.

IndieWire’s ‘70s Week is presented by Bleecker Street’s “RELAY.” Riz Ahmed plays a world class “fixer” who specializes in brokering lucrative payoffs between corrupt corporations and the individuals who threaten their ruin. IndieWire calls “RELAY” “sharp, fun, and smartly entertaining from its first scene to its final twist, ‘RELAY’ is a modern paranoid thriller that harkens back to the genre’s ’70s heyday.” From director David Mackenzie (“Hell or High Water”) and also starring Lily James, in theaters August 22.