The music! The dancing! The clothes! The hair! (Watch the hair!) Celebrating almost 50 years of the iconic “Saturday Night Fever,” Margo Donohue’s upcoming book “FEVER: The Complete History of ‘Saturday Night Fever’” is the first-ever complete history includes exclusive interviews, rare photographs, behind-the-scenes stories, and brand-new insights into the cult-hit phenomenon that’s been stayin’ alive for generations.

IndieWire shares an exclusive excerpt from Donohue’s book below, chronicling the musical chairs behind the film‘s directors, both original and eventual. The book will be released by Kensington Books on Tuesday, August 26.

With the screenplay being taken care of by Norman Wexler, producer Robert Stigwood hired John Guilbert Avildsen (professionally known as John G. Avildsen) to direct the film. Born in 1935 in Oak Park, Illinois, Avildsen’s father worked as a mechanic and spent his downtime making movies with his 16mm Bell & Howell Filmo camera. His English mother was an actor from Liverpool who taught Avildsen the importance of paying attention to the audience.

Working at an ad agency (with Wexler for a time) in the early 1960s, Avildsen made industrial films for clients as diverse as IBM and Jeep, learning to direct and edit his work quickly. This became his “film school” and his first pictures were “nudies” or “sexploitation” with titles like “Turn on to Love” and “Guess What We Learned in School Today.” They were cheesy but he gained enough experience to work for Cannon Films and bring his playwright friend for the ride.

Despite being only 5”5”, Avildsen on set radiated confidence and self-assurance. Some actors loved this, such as Jack Lemmon, who specifically asked Avildsen to direct him in 1973’s “Save the Tiger,” which won him his first acting Oscar since 1955’s “Mister Roberts.” In his career, he will direct seven actors for Academy Award nominations including Lemmon, Frank Gilford, Burgess Meredith, Sylvester Stallone, Talia Shire, Pat Morita, and Burt Young.

Avildsen was fired from a few projects in his life, which often happens during the initial set-up of films as people wind up with differing agendas. For example, with 1973’s “Serpico,” based on the life of real-life whistleblower detective Frank Serpico who fled the country after exposing the nefarious deeds of several New York City police officers. While the two became friends and Norman Wexler was hired to write the screenplay (his second Academy Award nomination) Avildsen balked at hiring producer Martin Bregman’s girlfriend Cornelia Sharpe in the role of Serpico’s girlfriend. He was let go and Sidney Lumet wound up directing.

His most famous work in 1976, when he signed up to direct “Saturday Night Fever,” was “Rocky.” Created by and starring Sylvester Stallone, the two were at loggerheads throughout the production. Stallone (a conservative) saw Rocky as a young man working hard to achieve his goals and liberal Avildsen saw it as a boxer fighting the establishment. With a $1 million budget, they went to shoot on location in Philadelphia on a twenty-eight-day shoot with a nonunion crew. Burgess Meredith plays Rocky’s trainer Mickey and Burt Young as Talia Shire’s (Adrian) brother Paulie. All would get acting nominations for multiple awards, but the big one was the 1977 Academy Award for Best Picture.

Meanwhile, executive producer Kevin McCormick was met with many rejections shopping around Nik Cohn’s New York magazine article “Tribal Rights of a New Saturday Night” to film studios which Stigwood bought specifically for John Travolta as part of a three-picture/$1 million deal with the 23-year-old sitcom actor who had dreams of movie stardom.

As he pitched agents and studios in Los Angeles when searching for a director, McCormick recalls hearing, “’Listen, kid. My clients do movies; they do not do magazine articles.’ And I literally booked my passage back to New York the next day and thought, I do not know what the fuck I am doing.”

Then his luck changed. “And then the phone rang, and it was this guy. ‘You’re in luck. The guy you wanted to get to was in my office today, and he read the article, and he is interested in a meeting, but you should see his new movie first. John will set up a screening for you all in New York,’” McCormick told me.

“So, we saw ‘Rocky’ and hired John Avildsen before that film even opened. And then our movie was developed, and Avildsen wanted to be the director, DP (director of photography), and editor as well. I mean, he literally wanted to have multiple credits,” he remembers.

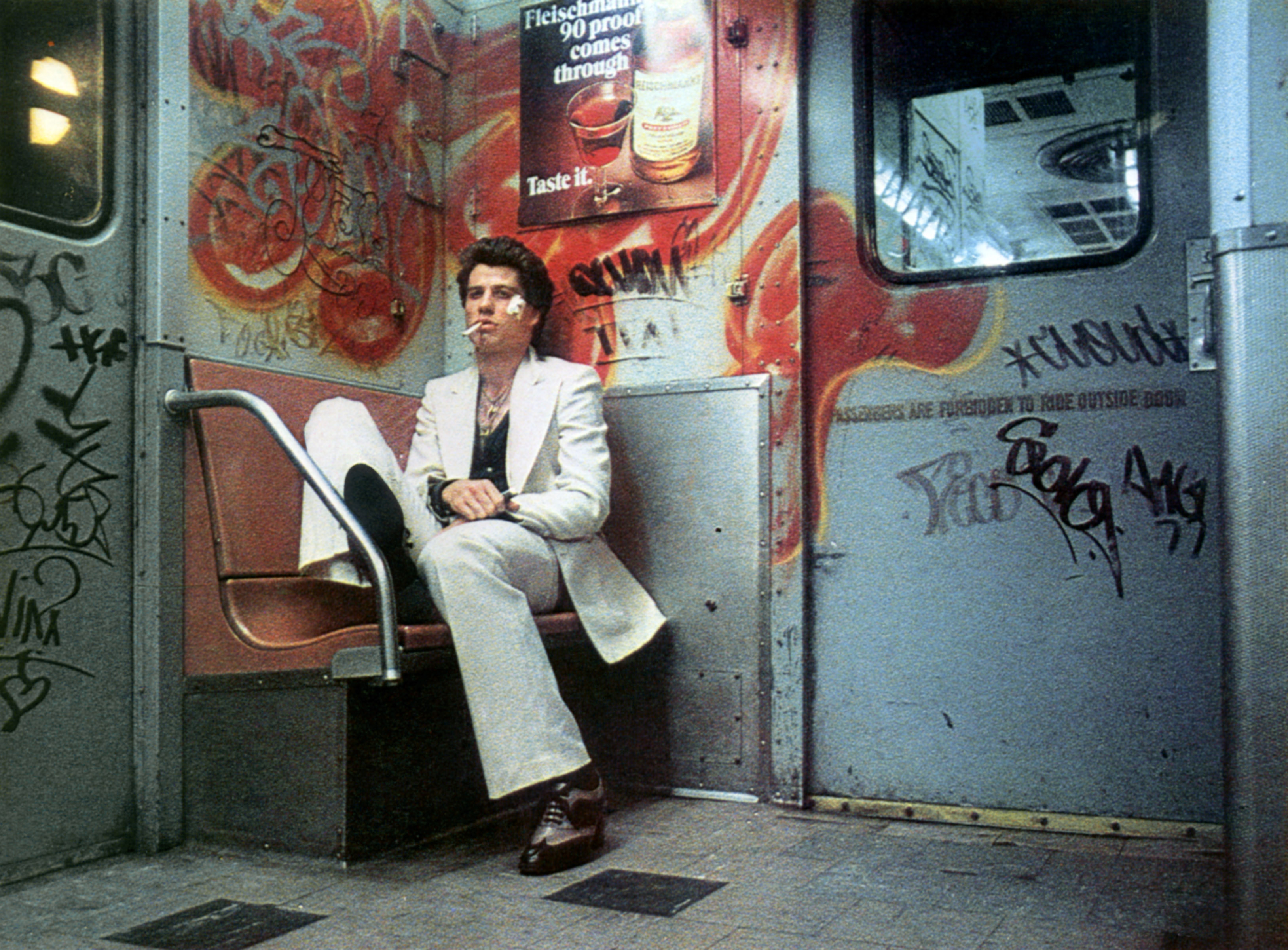

Having a feeling “Rocky” would be a huge hit, Stigwood at first catered to his new director’s ideas for script changes. Even though he and Wexler were close friends, Avildsen was not above taking over the screenwriting with his own version, which made the lead character of Tony Manero as more of a nice guy. The kind of person who helps old ladies with their groceries and warns kids about the dangers of drugs. Stigwood chafed at making anything less than a gritty film.

His first meeting with Travolta over breakfast at the Beverly Hills Hotel was the first stage of failure in his tenure as director. He looked down at the TV star and thought he had no sex appeal. He insisted that Travolta train with Jimmy Gambina, the boxing expert who had a role in “Rocky” (Mike) and helped set up the boxing sequences. This would help him lose the “baby fat” and they will worry about the dancing later. The star wanted to explore the script more seriously, but the director was adamant it would change to have a more positive outlook.

Then, after officially firing Norman Wexler, he started giving new pages to McCormick, who then passed them along to Stigwood. He recalls, “Avildsen was, going through a revolving door with writers, and the script was getting worse every time. And the last thing he gave me in the new script, ‘I have been thinking about the Bee Gee’s music. I just think they are over. You want something more contemporary.’ So, Stigwood called, and he said meet me at the airport tomorrow. So, I did, and I gave him the script.”

Stigwood was furious about Avildsen’s changes and instructed McCormick to set up a meeting at Stigwood’s Central Park West penthouse for ten the next morning, February 10, 1977. The executive producer recalls, “John and I were, like, twiddling our thumbs in the living room. Stigwood came in and he said, ‘John, nice to see you. There’s good news and bad news. The good news is you have just been nominated for an Academy Award, and the bad news is you are fired.’ And that was the quickest meeting I have ever been in.”

In the documentary, Avildsen blames his firing on the fact he was caught dating the “producer’s boyfriend’s girlfriend.” Wexler told the Los Angeles Times on June 12, 1977, “Avildsen was moving in a Capra-‘Rocky’ direction, all involved in sweetness and light.” The consensus is he was fired for wanting to change to film in a direction that Stigwood and Travolta hated. Wexler was brought back as screenwriter and McCormick had the task of finding a new director with three weeks left before production was set to begin.

Thirty-eight-year-old John Badham had an unusual background. He was a self-proclaimed “Army brat” who was raised in England and Birmingham, Alabama with a mother who starred in local TV shows and a stepfather who was a retired Army general. With a scholarship to Yale, he worked on several musical productions as a stage manager and actor. It was at college when he first saw Orson Welles’ “Citizen Kane” that made him consider working in television and film.

During his junior year, his nine-year-old sister Mary was cast as Scout in 1962’s adaptation of “To Kill a Mockingbird.” Based on the Pulitzer Prize 1960 novel by Harper Lee, the film starred Gregory Peck as Atticus Finch and Robert DuVall in his film debut as Boo Radley. Mary was nominated for an Academy Award, which gave her slightly jealous brother the urge to succeed on his own.

His resume was packed with television from “Night Gallery,” “The Streets of San Francisco,” to 1974’s “The Law” with Judd Hirsch and Bonnie Franklin which won him a Primetime Emmy for Outstanding Special. In 1976, he directed his first feature “The Bingo Long Travelling All-Stars & Motor Kings” starring Billy Dee Williams, Richard Pryor, and James Earl Jones. The story takes place in the 1930s and is a fictional tale about Negro League Baseball. It was scheduled for release in the summer of 1977.

In the meantime, he had been picked to direct the musical version of “The Wiz” with Diana Ross as the star. The hit Broadway show was an urban remake of “The Wizard of Oz” with Ross starring as Dorothy. Badham could not figure out how to film Ross (34 at the time) as a young girl and, feeling ill equipped to work around this conundrum, decided to get himself fired by offering a bizarre idea. In a production meeting he discussed shooting the entire film from Ross’ perspective. “We never see her — only her shoes, occasionally.” He was booted right away.

In February 1977, Badham was unemployed, separated from his wife, and suffering the worst flu of his life when his agent called him about a new job. He had read about Avildsen’s firing in Liz Smith’s column and wondered what was going on with the project now called “Saturday Night.”

He told me, “My agent said, now do not read it until I make a deal on this. So, of course, being the kind of person that does the opposite of what your mother tells you, I promptly started to read it. An hour later, whenever I finished it, I was cured. My temperature was normal. I am going around beaming, this is great. Oh, boy.”

He was hired immediately and, after a tense first breakfast meeting with Travolta, he assured him the film would be the vision they all think is best. That it will be smart, gritty, and heavily feature Travolta’s dancing, which he spent months working on. Travolta was eager to know the status of the female lead. Amy Irving and Jessica Lange were recently in consideration but other commitments (mainly Dino DeLaurentis, who picked Lange for the 1976 remake “King Kong” and would not let her out of her contract) and lack of chemistry with the meticulous star made it difficult to find the perfect Stephanie.

He also needed to hire the rest of the cast (only Travolta was locked in), finalize over sixty locations for shooting (including the nightclub), hire a choreographer, and then there was the Bee Gees part. When first meeting Stigwood, he handed him a cassette tape telling Badham, “There are three number one songs here.” It was an early demo of the Gibb brothers’ heavy soundtrack and Stigwood was wrong. There would be four number one songs on it.

Badham quickly flew to New York and his first indication on what a low budget film looks like — he was picked up by production manager Michael Hausman at LaGuardia Airport. According to Hausman, “In those days, you could actually drive to LaGuardia Airport and park your car right at the curb and go to the gate to meet somebody. John Badham came out of the plane, and I introduced myself.”

“We get to my car, which was a truck. It had a seat in the front and the back was a pickup. In front of my pickup was a limousine. And he started walking towards the limousine. And, I said, no, John. Here is a garbage bag that we are gonna put your suitcase in, put it in the back of the truck, and I am gonna drive you to the hotel. And for many years now, whenever he talked about making that movie, he said, that was Mike’s way of telling me who is in charge and what it is gonna be like,” he recalls with a laugh.

From “FEVER: The Complete History of ‘Saturday Night Fever,’” by Margo Donohue. Reprinted with permission from Kensington Books. Copyright 2025.

IndieWire’s ’70’s Week is presented by Bleecker Street’s “RELAY.” Riz Ahmed plays a world class “fixer” who specializes in brokering lucrative payoffs between corrupt corporations and the individuals who threaten their ruin. IndieWire calls “RELAY” “sharp, fun, and smartly entertaining from its first scene to its final twist, ‘RELAY’ is a modern paranoid thriller that harkens back to the genre’s ’70s heyday.” From director David Mackenzie (“Hell or High Water”) and also starring Lily James, in theaters August 22.