It’s early days at the Venice Film Festival, but there seems to be an emerging theme of the dehumanizing nature of work under late capitalism (see also: “Bugonia” and “No Other Choice”). French actress an director Valérie Donzelli has a very specific riff on this theme in “A Pied D’oeuvre (the English title is literally “At Work”), her modern riches-to-rags tale about a man who gives up life as a successful, well-remunerated photographer in Paris in order to scrape a living as a casual laborer and use his free time trying to become an author that his children want to read.

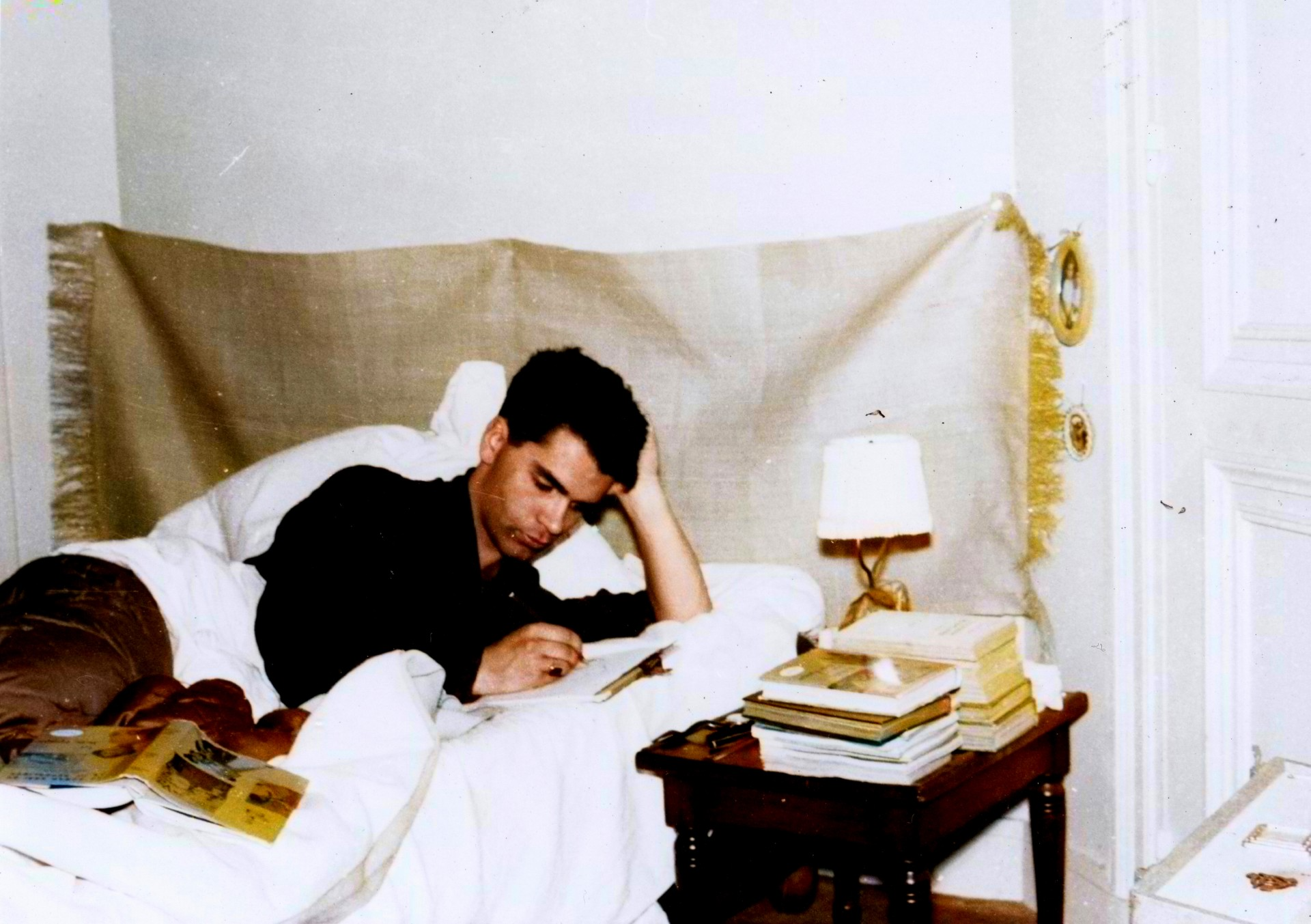

Paul (Bastien Bouillon) is taking a hammer to drywall when we meet him, as the life he used to know is shattering into pieces. At the age of 42, he has switched creative lanes from being a photographer pulling in €3k to €8k a month to being a writer who has already spent the advance on his unpromising third book. Meanwhile, his recent ex-wife (Donzelli) has moved to Montreal along with his son and daughter and Paul has moved out of their large house into a tiny studio. His thinly veiled account of the breakdown of their marriage, “The Story of the End” his agent deems unsaleable. If being a good writer means living in such a way that the material generates itself, then Paul’s life and vocation are both in need of an overhaul.

Paul wants to find the kind of work that leaves him enough time to write, and this is how he ends up on the “Jobbing” website, setting up a profile and listing his manual labor/ handyman skills. Donzelli’s unflashy style of direction has a brisk simplicity, letting observational details play out without underlining them, so that mildly comic moments could just as easily have you grimacing in recognition. The tiny ghost of a smile that Paul performs to his webcam for take two of his profile picture is the world in a grain of sand, reflecting the fact that it’s not enough for people to sell their labor, they must appear to emanate a deep sense of well-being from within while, say, dismantling a mezzanine or mowing your lawn.

This is a film parked out in the minutiae of Paul’s new work culture and attuned to the fact that, when your work is underpaid, you can never get enough of it. Members of the Jobbing website are pinged whenever a job within their skillset is listed, at which point, it’s a bidding war to the bottom as jobbers set their rates ever-lower. Paul commonly bids at €20 for jobs that take hours, meaning his rate is nowhere near the wheelhouse of minimum wage.

Still, as he reflects, he has a beginner’s zeal to make this system work, and that gives him an advantage over more disenfranchised jobbers with a long-term dependency on it. Adapted from an autobiographical novel by Frank Courtes, the film is in the trenches of Paul’s personal experience while retaining the perspective that most people who turn to Jobbing do so out of desperation rather than idealism. Unlike the migrant workers that he competes with for jobs, Paul is still in receipt of humble monthly royalties. “€200-300 a month is not poverty but it gives a clear view of it,” he writes. Although Paul has relative privilege here, relative privilege does not pay the heating bills and it is clear — through the glimpses of debasement that occur with increasing frequency — that our hero is flirting with ruin.

The people around him berate him for his choices, his sister says that he is not a “real” poor person and asks why he doesn’t get a different job. Verbalising the idealism that quietly motors under the surface of both the film and its protagonist, Paul says that “some slaves are well-paid today.” He has tasted the life that a corporatized creative job can buy and has found it lacking. His newfound precarity is not romanticized, it is presented as the necessary alternative to a less suitable path. He is taking Robert Frost’s road less traveled in the hope that it will make all the difference.

Half-way through the film, he has an encounter with the man he used to be, which is to say, in his capacity as a driver, he picks up a man that he knew from the photography world. Over dinner, this man, who still has a well-paid job, a big house, and luxe travels, offers a graceful understanding of what his former peer is doing and contrasts it with his own “hyper-consumption. … You’re cutting down, it’s good.”

The narrow narrative framework is undergirded by a taut, eloquent script by Valérie Donzelli and Gilles Marchand (whose previous writing credits include Cannes 2025 titles “Enzo” and “Case 137”). The ring of lived experience does not hamper or labor this clear-eyed depiction of a man whose desire for freedom might see him free-fall into a different trap: poverty.

Virtually a one-man-show, Bouillon carries the film aided by the kind of face that looks different from every angle. His clients are curious about him. “You don’t look the part,” says one woman as he arrives in his cable-knit sweater and owl glasses to construct her armoire. The glimpses of the people that he meets in this new line of work feed his writely imagination and he reconstructs them on the page. Fears that the narrative will end in a cliche, with Paul writing a book about being poor that makes him rich again, are thankfully unfounded as the film deftly avoids any such trap.

If this modest fable feels slight in a competition dominated by filmmakers swinging for the fences, then it’s not for a lack of substance. Full of throwaway insights into the micro-climate of a particularly hellish economic landscape, “At Work” is an engaging story about a man trying to write an engaging story with a diamond of hard-won wisdom at its core.

Grade: B+

“At Work” premiered at the 2025 Venice Film Festival. It is currently seeking U.S. distribution.

Want to stay up to date on IndieWire’s film reviews and critical thoughts? Subscribe here to our newly launched newsletter, In Review by David Ehrlich, in which our Chief Film Critic and Head Reviews Editor rounds up the best new reviews and streaming picks along with some exclusive musings — all only available to subscribers.