There’s something magical about a soufflé. It is infamously tricky to make, requiring patience, precise temperatures, and meticulous technique. A perfect one needs to combine rich creaminess with feather-light airiness, balancing indulgence with ephemerality. Its existence has been passed down from generation to generation to those who seek to preserve a piece of culinary heritage, explaining the importance of a 45-degree angle spoon to fold, the correct whisking technique, and the precise texture required at each step to result to form crisp outer layers and an oozing center.

As such, the soufflé has long served as a kind of culinary metaphor for highly skilled folly, something nutritionally inconsequential, fleeting, but nevertheless a testimony to its creator’s craftsmanship. You marvel at it, even as you wonder whether it was worth the effort.

In the aptly named “The Souffleur,” this metaphor speaks to both the film’s strengths and weaknesses. Gastón Solnicki’s latest work features a magnetic central performance from Willem Dafoe, it is artfully composed with painterly images, shots of Vienna at sunset are exquisite, and its spartan dialogue possesses a dry wit. Yet for all its craft, the film remains airy and unsubstantial, never quite rising to the full potential of its premise. Like its namesake dish, it is something to admire in the moment, but it evaporates quickly, leaving you more confounded than satisfied.

The film begins with archival footage of the groundbreaking of Vienna’s InterContinental Hotel, once considered the pinnacle of European luxury. At the time of its construction, it was hailed as the greatest hotel in the world and, we are told, was the first to boast telephones in every bathroom. Fast forward to the present, however, and the grand dame has faded. The chandeliers still sparkle in the ballroom, but the carpets have yellowed, the façade has rusted, and the famous rooftop sign is now a weather-beaten relic. Even the employees, once the guardians of glamour, linger on smoke breaks with the weary disaffection of people simply marking time.

It is in this fading palace that Lucius Glantz (Dafoe), the longtime manager, continues to preside. Having raised his daughter Lilly (Lilly Lindner) within its walls, with the staff functioning as an extended family, Lucius clings to the institution with a faith that borders on delusion. His entire identity is woven into its hallways and kitchens, and the news that an Argentine mogul — played with ironic detachment by Solnicki himself — intends to purchase the hotel and demolish it to make way for a new architectural venture is treated as nothing less than an existential threat.

From here, “The Souffleur” sets out an intriguing promise: that, in the absence of a tangible purpose, we will witness one of Dafoe’s signature descents into the unhinged, mirrored against a Vienna that itself seems adrift and hollowed out. Solnicki’s Vienna is not the city of Strauss and café culture, but one drained of vitality. Parks are filled with abandoned football goals, tennis matches drag on with no one able to score a point, and the hotel basement brims with strange, steampunk-like machinery that screams obsolescence. Time itself begins to falter — clocks spin strangely, pipes clog without reason, and most tragically, Lucius’ once-perfect soufflés have gone from magical to inedible.

These surreal flourishes give the film a dreamlike atmosphere, but they also highlight its limitations. Much of the narrative weight falls entirely on Dafoe, and while he is as fascinating as ever — his gaunt face capable of both menace and mischief — the other characters are left as sketches. They break the fourth wall to introduce themselves, but reveal almost nothing beyond their preferred drinks. Even the Argentine developer, briefly gifted a narrated montage of his childhood fascination with the hotel, never seems to acquire a coherent motive or personality. The eventual confrontation between him and Lucius is staged as if it carries mythic significance, but it arrives oddly deflated, neither dramatically explosive nor thematically clarifying.

What works best are the moments of humor, particularly those that seem to wink at Dafoe’s own eccentricities. His narration is a constant pleasure — mournful, wry, and suffused with a world-weary poetry. There are few actors whose disembodied voices could carry long stretches of cinema, but Dafoe manages it, turning monologues about marionette mechanics or muttered complaints about hotel politics into something weirdly magnetic.

Still, for a film so light on plot and so committed to gently lamenting a glorious past that can never be restored, “The Souffleur” struggles with precision. At 76 minutes, it risks feeling both overextended and underdeveloped: too meandering to deliver a sharp parable, yet too short to explore its characters and ideas in real depth. One senses that Solnicki wants to make a film about loss — loss of purpose, of grandeur, of relevance — and to tie it to questions of mortality and legacy. But he approaches these themes obliquely, with a shrug more than a scalpel.

The result is a film that glimmers with moments of wit and melancholy but never settles into coherence. Like a soufflé, it is beautiful in concept, fragile in execution, and destined to collapse the moment you press into it.

Grade: C

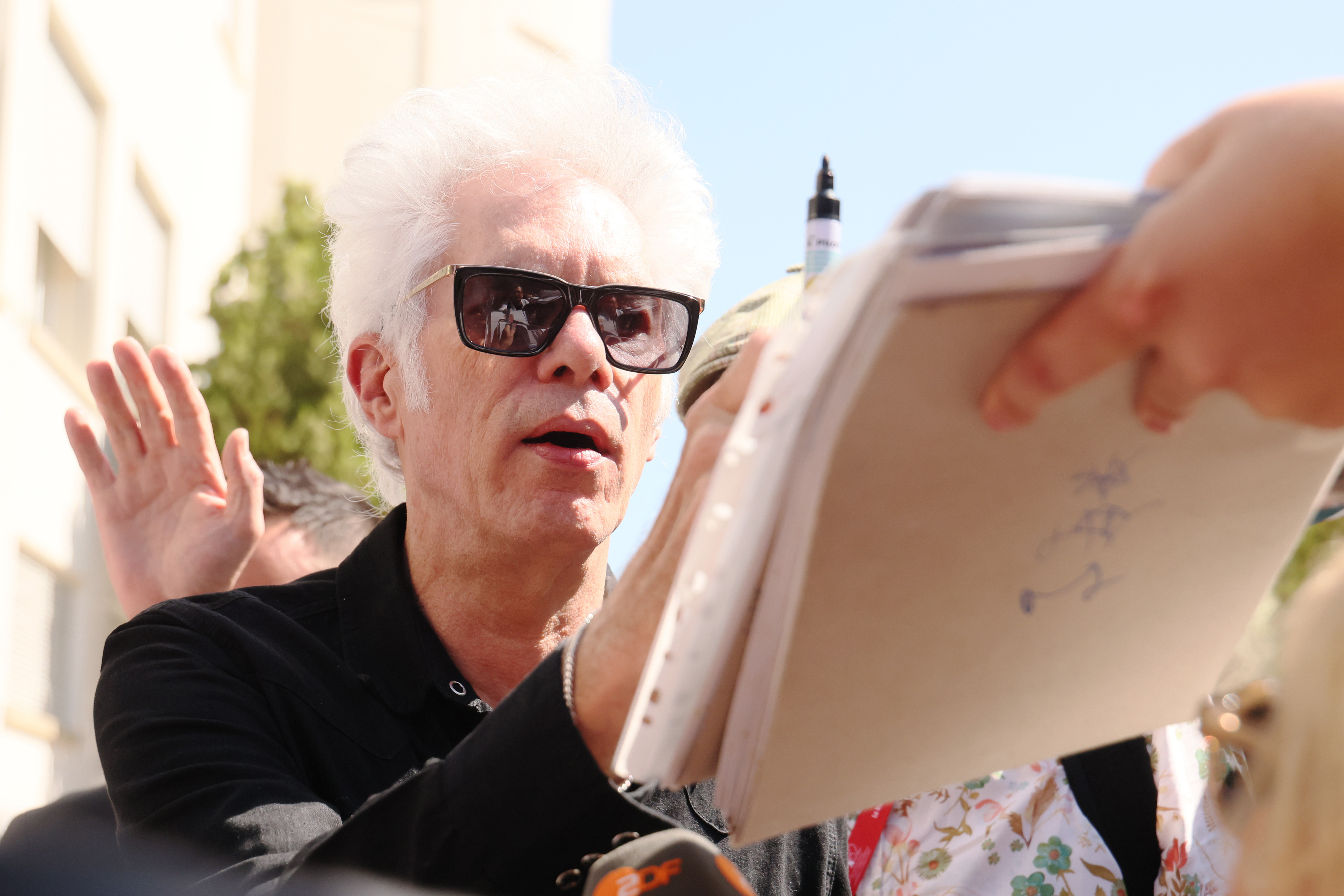

“The Souffleur” premiered at the 2025 Venice Film Festival It is currently seeking U.S. distribution.

Want to stay up to date on IndieWire’s film reviews and critical thoughts? Subscribe here to our newly launched newsletter, In Review by David Ehrlich, in which our Chief Film Critic and Head Reviews Editor rounds up the best new reviews and streaming picks along with some exclusive musings — all only available to subscribers.