In many respects, the 2023 Caquetá Cessna Stationair crash feels like a story tailor-made for a National Geographic documentary. It has everything you expect from a movie from the channel: human survival against the elements, plenty of nuanced political and cultural context to dig into, a heart-wrenching backstory to untangle slowly through the film, and lots of breathtaking nature b-roll.

The movie that NatGeo ended up producing about the event, “Lost in the Jungle,” is coming a bit late to the party — Netflix beat them to the punch by about a year with their telling “The Lost Children” — and doesn’t really register as a standout from the company’s portfolio. But the subject matter is compelling enough, and the filmmaking sturdy enough, that it’s an engrossing watch despite its minor flaws.

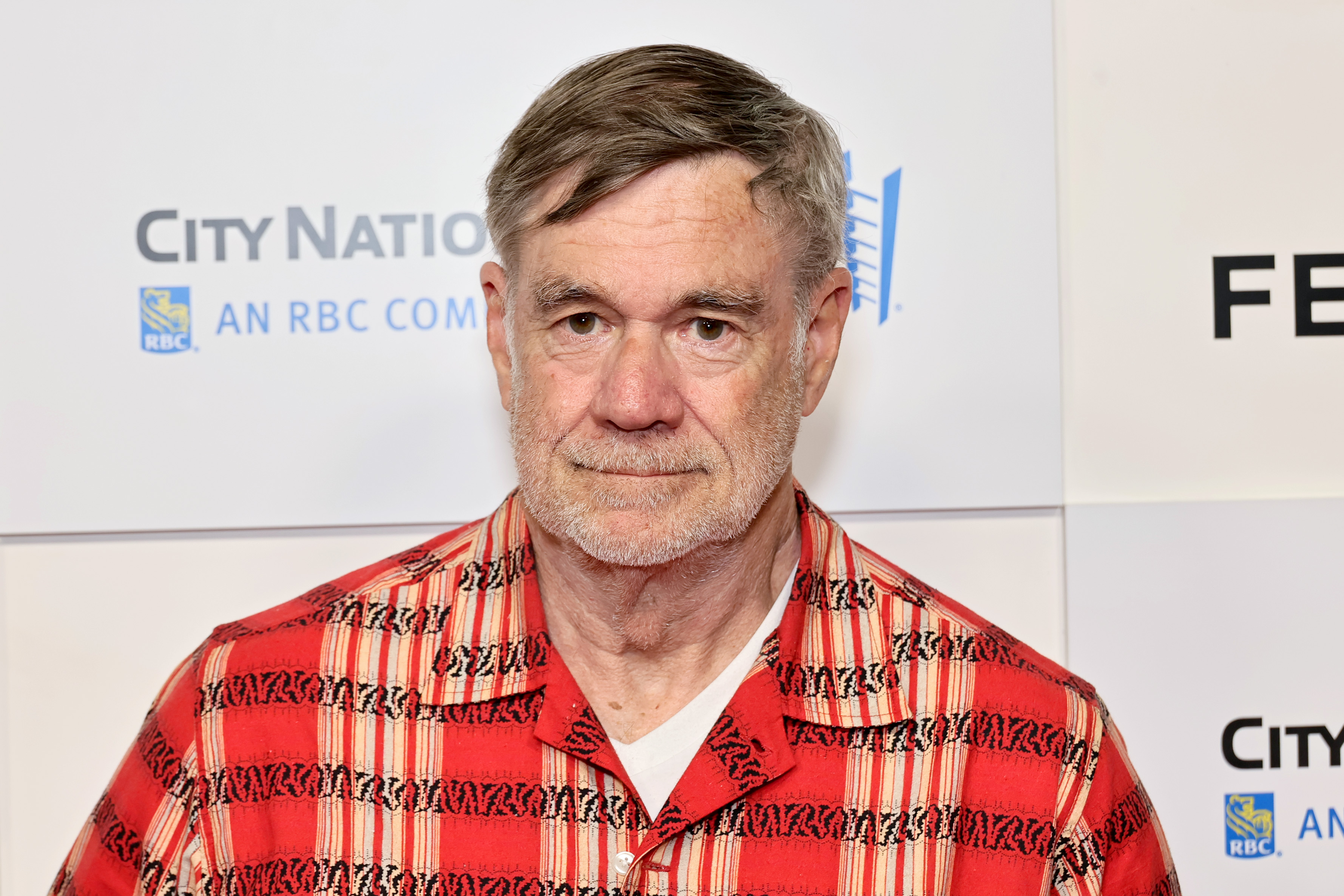

“Lost in the Jungle” was directed by the now-divorced husband and wife directorial team Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi and Jimmy Chin, collaborating on this film with Juan Camilo Cruz. Vasarhelyi and Chin are no strangers to National Geographic, having helmed one of the company’s biggest hits in 2018’s “Free Solo,” a adrenaline-pumped and gravity-defying account of one man’s attempt to scale El Capitan.

Compared to that Oscar-winning production or their other films like “The Rescue” for NatGeo, “Lost in the Jungle” is a bit more meat-and-potatoes in its presentation, stringing together talking heads, darkly lit recreations, and some rare taken footage to recount the 40-day search from authorities to find four children gone missing in the forests of Colombia.

Opening with a (somewhat sluggishly staged) reenactment of the inciting incident, “Lost in the Jungle” lays out the facts of the tragedy quickly. On May 1, 2023, indigenous Witoto woman Magdalena Mucutuy Valencia boarded a charter plane to the town of San José del Guaviare, where she intended to surprise her husband Manuel. In the air over the Amazon rainforest, the plane experienced engine failure, and crashed, killing her, the pilot, and local indigenous leader Herman Mendoza Hernández. The only survivors were Magdalena’s four children, ranging from ages 13 to infancy, who were left stranded and injured in the wilderness with no idea of how to escape.

For those unfamiliar with the incident, there’s (perhaps thankfully) little tension that the kids will be found and rescued. Peppered throughout the film are sections narrated by the eldest daughter Lesly, recounting the animals and dangers the kids encountered during their long period stranded in the forest. In the film’s only real visual flourish, these scenes are animated usually translucent, see-through animations set against b-roll of the real forest. It’s not a wholly successful approach — it has an oddly distancing effect from the realities of their hopeless predicament — but attains moments of real visual beauty.

Elsewhere, “Lost in the Jungle” does the groundwork to get you invested in the tragedy, and thankfully avoids treating Magdalena as a pure afterthought. Flashbacks and interviews with friends and family members slowly paints a portrait of a loving mother and a fun, vibrant woman, as well as the abuse she and her kids suffered at the hands of Manuel, the father of her two youngest and stepdad of Lesly and her brother Soleiny. Manuel himself is featured in interviews, and while the film gives him plenty of space to share his side of the story and his involvement in the rescue campaign, it also never lets his misdeeds off the hook — in one poignant moment, a family member speculates that the sound of their father’s voice might compel the kids to hide from the rescue team.

The real sauce of “Lost in the Jungle” comes from its documentation of the grueling search effort to find the kids, which in reality was two rescue missions: one from a Colombian Special Forces crew that descends upon the rainforest in helicopters looking for the kids, and one from the various indigenous communities of the area who use canoes to roam the rivers and their vast knowledge of the Amazon as a tool for searching. Initially encountering each other in their separate groups, the two parties are distrustful and disdainful of one another, and “Lost in the Jungle” uses this incident to explore a historical divide between the indigenous communities of the Amazon and the Colombian government that dates back to the rubber trade of the 19th century, which resulted in the enslavement and genocide of millions. In modern times, tension between the groups still exist, thanks to guerrilla units that control the territory of many indigenous groups.

As the documentary depicts through footage of the rescue efforts, all of those outside tensions make the two rescue parties reluctant to work together, until the government orders the special forces team to use the indigenous search party’s knowledge of the forest in their favor. Through interviews with members of the special forces team, “Lost in the Jungle” tracks how the military men slowly grew more open to and accepting of their very different counterparts, and how the group’s collaboration eventually proved essential to the success of the mission. And to its credit, “Lost in the Jungle” mostly manages to avoid the trap of portraying indigenous culture purely through the eyes of the white Colombians, giving them plenty of interviews to speak about the spiritual practices they used to aid in the search.

If there’s any issue with “Lost in the Jungle,” it might be that there’s too little of it. At 90 minutes, the film is quick and efficient, but it leaves little time to explore more about the collaboration between these two search parties, or the unsteady relationship between the region’s indigenous communities and the narco-guerrilla units ruling over them. The film ends on a note of hope, explaining where the children have ended up in the years since and culminating in footage of a Colombian official giving a speech about how the search should start a new phase of understanding between the government and the indigenous communities. It’s a somewhat pat, overly rosy broad-strokes ending to a story that’s certainly engaging and well-told, but also had the opportunity to go deeper than itself.

Grade: B-

“Lost in the Jungle” premiered at the 2025 Telluride Film Festival. It will air on National Geographic on Friday, September 12 before streaming on Hulu and Disney+ starting on Saturday, September 13.

Want to stay up to date on IndieWire’s film reviews and critical thoughts? Subscribe here to our newly launched newsletter, In Review by David Ehrlich, in which our Chief Film Critic and Head Reviews Editor rounds up the best new reviews and streaming picks along with some exclusive musings — all only available to subscribers.