Contains spoilers for “Foundation” Season 3, Episode 7 — “Foundation’s End”

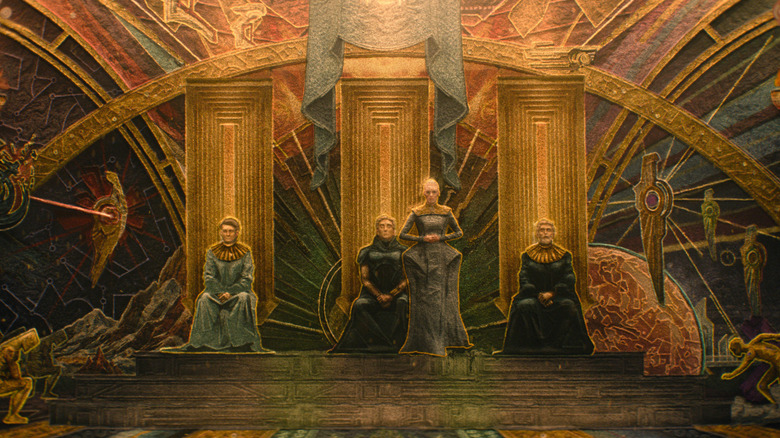

“Foundation” Season 3 continues to barrel on toward its epic climax as Laura Birn’s android Demerzel seeks a safe future for humanity and Pilou Asbæk’s mind-bending villain, the Mule, actively works against that goal. Episode 7 continued to set the stage for the upcoming finale — this time through a look back at the origin story of the villain himself. The episode opens with a sequence on the Outer Reach, on an out-of-the-way planet called Rossem. By the end of the episode, we’ve learned that the anarchic villain was shaped by a horrifying betrayal that involved attempted murder.

The Mule’s surprising backstory (which deviates from the source material in a major way) is the main takeaway from the episode, but major fans of “Foundation” author Isaac Asimov may have noticed that the planet Rossem also contains a fun little Easter egg in its name. It’s very close to another major word that influenced Asimov’s world: Rossum. The importance of that name? It’s directly connected to the genesis of our modern word robot. That’s right — while Asimov popularized the word robot in the 20th century, he didn’t make it up. He took it from a Czech play called “Rossum’s Universal Robots,” or simply “R.U.R.”

Rossum’s Universal Robots

In his book “Robot Visions,” Asimov explains how, the year after he was born, Czech intellectual Karel Čapek debuted his play “Rossum’s Universal Robots.” At the time, the term “robot” was unknown, but that was about the change. Here are Asimov’s direct words about the production: “The play was produced in 1921 and was sufficiently popular (though when I read it, my purely personal opinion was that it was dreadful) to force the word ‘robot’ into universal use. The name for an artificial human being is now ‘robot’ in every language, as far as I know.”

Čapek didn’t just pull the word robot out of thin air for “R.U.R.” It came from the Czech word “robota,” which means forced labor, and is historically associated with serfs, agricultural laborers contractually tied to the land of their lords. The root of the word is even more chilling: “Rab” is Czech for slave. Despite Asimov not being impressed when he later read it, the play was a smashing success, initially being translated into 30 languages. A century on, we still hear its echoes, most notably in the works of the man who took the robot concept mainstream.

Remarkably, the role of robots (and the people who make them) in science fiction hasn’t changed all that much since their inception. Speaking after the premiere of his play, Čapek explained what drove the titular inventor. “Mr. Rossum (whose name translated into English signifies ‘Mr. Intellectual’ or ‘Mr. Brain’) is a typical representative of the scientific materialism of the last [nineteenth] century. His desire to create an artificial man — in the chemical and biological, not mechanical sense — is inspired by a foolish and obstinate wish to prove God to be unnecessary and absurd.”

Does Rossem feature in Asimov’s writing?

Hardcore Asimov fans will be well aware that the name Rossem is not an invention of the “Foundation” TV series, though the version that appears on screen is different to the one from the source material. The author’s original print version of Rossem pops up in the book “Second Foundation,” but this time, it isn’t the home world of the Mule. Instead, it’s a planet that the Mule’s men visit while searching Hari Seldon’s secret Second Foundation. This world is radically different from the lush agricultural world we see in “Foundation” Season 3, Episode 7.

In the book, Asimov introduces Rossem by saying, “Along the chilly wastes of Rossem, villages huddled.” He says it has a small sun and that “snow beat thinly down for nine months of the year.” He goes on to explain the stingy three-month wheat growing window and how the grain is supplemented by goat’s milk and meat. Not the best environmental conditions for a happy life. But there it is. The word Rossem is in both the source material and the “Foundation” show, in both cases hinting at the inventor of a term that has become as commonplace as modern technology itself.