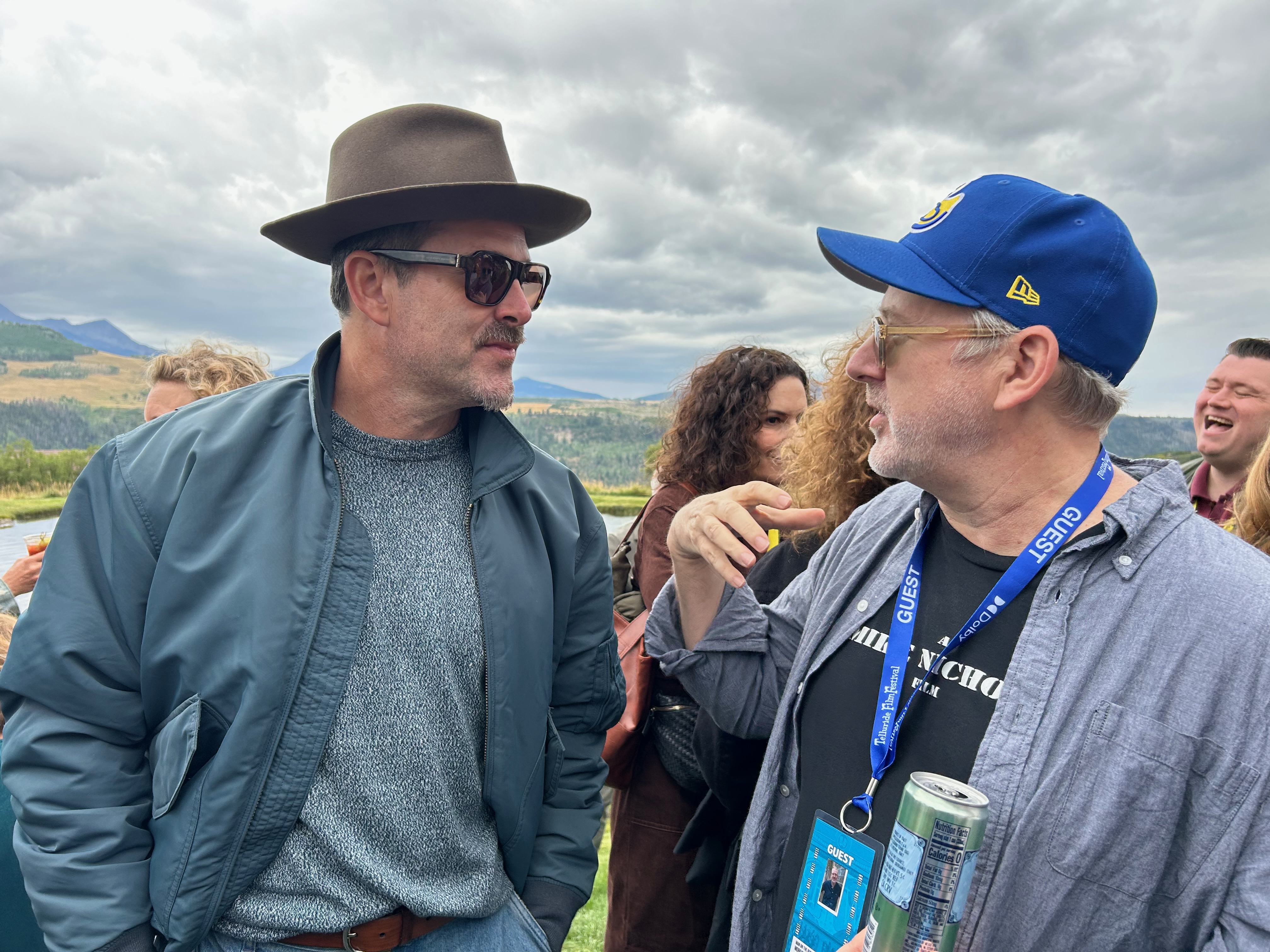

Listening to documentarian Morgan Neville and actor Paul Mescal dive down the Paul McCartney rabbit hole at the Telluride brunch was one of my festival highlights. Both are McCartney experts at this point, as Mescal is returning to rehearsals in London to play Paul in the first of Sam Mendes’ four Beatles movies, and Neville has spent the last three years prepping “Man on the Run,” his post-Beatles portrait of McCartney as he created his solo albums and assembled the band Wings. When I was growing up in ’70s New York, I loved McCartney albums Cherry and Ram, but was never a Wings fan. Now I see how many of his catchy songs have seeped into the culture: I’m adding a bunch to my playlists.

“Man on the Run” reveals an artist who must reinvent himself without the Beatles and with his great ally and love, Linda McCartney. But he never fell out of love with John Lennon.

This is a Q&A with Neville by documentary filmmaker David Wilson that took place after the film‘s second screening on September 1. (Full disclosure: My daughter works for Neville’s Tremolo Productions.)

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

David Wilson: You’ve worked primarily in music films, although every time you make a film about music you’re coming at it from a different place. What role did music play in your life growing up?

Morgan Neville: A lot. We had a jukebox in my house. Lot of Beatles 45s. My dad was a music obsessive. He saw the Beatles in ’64 in Indianapolis. I started playing music. I formed my first band when I was 12. My wife and I played in a band together. I just love music. And I love the stories of music, too. And I have made a lot of music films, but to me, they’re all exploring some different thing I’m trying to find out about.

That is a through-line in your films. With all these different subjects, there’s a big idea you’re grappling with. Is that something you think about going in? Or it comes out as you make it?

It’s both for this one. When I first started thinking about it, I started reading that first interview Paul gave, which was the Q&A where he revealed that the Beatles were no more. And you see the woman handing that Q&A out to the press. And that last question: “What are you going to do next?” And he said, “My plan, my only plan, is to grow up.” And I thought, “That’s the question I want to start with. What does that mean when you’ve been a Beatle since you were 17, you’ve been a quarter of this entity that’s gone to outer space and back. And how do you be a person in the wake of that?”

I’ve made a lot of biographical films. The films are always a form of therapy for me, and certainly for the subject. And with Paul, we could talk about that, trying to get him into a certain headspace. But the questions Paul was asking at that time were questions I was always wondering about: “How do you wrestle with your own legacy? How do you stay grounded in show business? How do you deal with being a parent and a father?” All these different questions that I grapple with all the time. So all that was resonating. So even though it’s Paul McCartney, who’s a genius to me, it was this guy who’s just an artist trying to find his way and trying to listen to his gut as much as he can. So “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” which is the flip side of “Mull of Kintyre,” they’re both crazy ideas. One turns out and one doesn’t, but it’s the same impulse, and I totally respect that fearlessness.

McCartney also talks about a quest for “personal peace.”

Yeah, and that quote at the end where Stella [McCartney] says, looking back on it, these were the happiest years of our lives? And I just sent my last child off to college 10 days ago. I get emotional even thinking about it. I don’t think anybody’s ever understood what Linda meant to Paul in all ways. And that’s what my wife means to me: having somebody who can be your wingman in every imaginable way, who has your back, is the greatest thing. That’s what you need to survive.

Had you met Paul before this project?

I met him once for a shoot on another documentary years ago. And then I met him again when we talked about the film, and he was, “Okay, this sounds great.” The first interview, we did in London at his office. He had a sound man in the Bates Studio in the basement. He said, “My guy will set up some mics.” So I show up, and there are two mics in this tiny love seat in his office. I’m sitting close. Okay, you have to forget it’s Paul McCartney and just go for it. And Paul’s great at helping you forget he’s Paul McCartney, because he’s been Paul McCartney for a very long time. For somebody like him, who’s been public for so long, who’s talked so much, to not do the jukebox of greatest hits, of things he says about albums or songs, and trying to really break that, was great.

I did many audio interviews, but I wanted to have conversations with him. So we started talking about ideas. We talked about painting, we talked about all different kinds of things, because I wanted to get him to be thinking and speaking in the present. That helped. He recognized in the conversations he would get carried away. We ended up having seven sessions of interviews over more than a year.

The Beatles are famously difficult interviews, right? Was there a moment with him, as you were in those sessions, where you thought, “Oh, this is something new. I’m getting a side of Paul that wasn’t there.”

I like to think so. When he would get excited about things, we were doing one interview at his house, and he’d run over to the piano and start playing, show me stuff. And then he’d go on about getting high with Fela Kuti. It was helpful to get him in a certain headspace. He hadn’t talked about Linda in any deep way in decades. I just showed the film two weeks ago. He had a little family screening with his family and all the grandchildren, and invited my wife and my son. All the grandkids are sitting in front of me. Stella’s son said, “I’ve never heard my grandmother’s voice before,” and that punched me. And then I heard another grandson say, “Grandpa went to jail?”

Was there a moment where you thought you would go all the way up to Linda’s death?

I always felt like that decade and the bookends of McCartney, one and two: leaving the Beatles and John’s passing, and running away from the Beatles and what he had done for that decade. And I definitely thought about Linda’s death and we played with it, but it just felt extraneous in a way that Linda did live on for another 17 years past this time. And when I showed Paul the film, he said, “I’m so glad that you left Linda at the end of the film like that.”

It’s something I’m piecing together from talking to Paul again just a couple weeks ago, in the beginning of the film where he said, “I thought myself as the bastard, when people blame me for all this.” He internalized it, and that period of ‘Let It Be,’ and then suing the band was so painful. And the “Get Back” project actually opened up something in him, saying it wasn’t all bad. Everybody said everything was horrible, but actually it was much more nuanced. There was love, there was tension. And that process of self-forgiveness was the reason this film happened: if that wasn’t that bad, maybe I should think about this other period that I’ve also pushed out of my head in a lot of ways. And that’s amazing that still 50 years later, that’s still going on.

The parallel love story here, obviously, is him and John. Do you think that “Get Back” experience opened up his ability to talk about him and John?

In watching ‘Get Back,’ which I devoured as soon as it came out, you see how much real love that he still has, to the point where John is in his life every day. And I’m not exaggerating. I have no doubt he thinks about John every day, if not many times a day. So it’s not something that’s distant to him. It’s something that he holds onto.

When you’re digging through an archive and trying to find something usable, and then this clip rises up to the surface, what were those clips for you?

God, there’s so many. Paul has an amazing archive. He married a photographer, so that was convenient, all of Linda’s negatives of that entire decade, which is just incredible. There are so many things in this film that have never been seen. And there’s so many tiny things from the way people talked about Paul in the press at the time. I love that little clip of the reporter going back to the Cavern Club to interview the young punk girl about the Beatles. The best thing is the home movies. Who documents themselves that much? Now, we maybe do with phones, but you see Paul filming with a 16 camera. And Linda’s taking pictures of Paul taking film of her.

There are so many great shots in this film of the actual construction of songs, where you’re in the studio, and you’re seeing them work through something. Was that something you specifically went looking for? How much did you want to have that behind the scenes?

I geek out on that stuff. And hearing the studio chatter. You can hear him orchestrating this stuff in his head in real time, which is what makes him Paul McCartney. And we have fragments of so many different songs in here. I loved the Beatles, but Wings were the band that were putting out albums when I was a kid, and that’s what I was buying. And I loved Wings. There’s so much interesting, good work through that decade that people don’t think about that much. He put out 10 records in 10 years. One of the happiest things was after I showed my son the film two weeks ago, I saw that he quietly added a whole bunch of Wings songs to his playlist on Spotify.

One of the joys was every three minutes there was hit after hit song that has been a part of the fabric of our world. Even if we didn’t identify with them the same way that we did with The Beatles.

We put that tiny snippet of “Wonderful Christmastime” in there, because in the midst of all that other stuff, that was a tiny single he threw out at the end of the year in 1979 which was a footnote, but a song that for better or worse we hear every year. It’s both the contextualizing and rediscovering of a lot of the songs we know, a deep dive, going through some of these records. And Ram is one of my favorite albums. It’s amazing how reviled that album was, again, you see the savage Rolling Stone review by Jon Landau, who went on to manage Bruce Springsteen. And now Ram is one of the top 500 Albums of All Time, according to Rolling Stone. So it’s that long game: Let’s not pay attention to what people want this week, this year. Let’s just make music that works for us.

How can people tell their friends to go see this?

Amazon/MGM bought the film and it’s not going to come out till February. Six months from now, hopefully you will hear all about it. We’re going to do a theatrical release, and then it will eventually stream. It’s coming.