Late in Hunter S. Thompson’s 1971 lysergic travelogue “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas,” the writer experiences something of a psychic vision of the end of the 1960s, a time he describes as “riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave” that led toward transformative social change thanks to worldwide protests for civil rights, an end to the Vietnam War, women’s liberation, even the subtler cultural shifts embodied by the rise of rock as the respectable music of youth.

And then, the harsh reality of the Nixonian “silent majority” reasserted itself, upending hopes of a genuine revolution with a reactionary backlash that rapidly disillusioned idealistic youth. “So now, less than five years later,” he writes, you can go up on a steep hill in Las Vegas and look West, and with the right kind of eyes you can almost see the high-water mark — that place where the wave finally broke and rolled back.”

That wistful, numb admission of defeat not only summarized the mood among the counterculture at the time, but also anticipated the shift over the 1970s away from the collective struggles of the prior decade to the cynical individualism and consumer therapy of the “Me Decade.” Cinema in the United States and abroad would tackle the various forms of political and psychological fallout of this ideological shift for much of the decade, but it is the movies that were made right at the dawn of the ‘70s that best capture the fresh dissociation of seeing change within one’s grasp, only for it to disappear before your eyes.

Just as Thompson saw something of the end of the hippie dream in the barren stretches of Southwest sand, so too did many of the American films most explicitly concerned with the collapse of ’60s idealism take place in the country’s deserts. Fittingly, one of the most piercing such depictions came from Italian auteur Michelangelo Antonioni, whose “Zabriskie Point” relocates many of the modern anxieties of his native Italian work to the flailing American protest movement and finds in the oppressive environment of Death Valley an echo of the volcanic Mediterranean isle central to his breakthrough “L’Avventura.”

The film begins with familiar sights of the implosion of 1960s counterculture: student activists have succumbed to factionalism that leaves them wide open to police suppression, and the trio of young leads — dropout/possible cop killer Mark (Mark Frechette), drifter Daria (Daria Halprin), and rich kid Lee (Rod Taylor) — meet and form a listless polycule that, in one hallucinatory sequence, expands outward into an orgy of young people entwined all over the hills. Antonioni’s critical distance from this mass display makes something of a grim parody of the Sexual Revolution, suggesting that its liberatory possibilities have been forgotten in the name of titillating distraction.

Antonioni builds his critique to a mesmerizing finale in which Daria drifts in a traumatized haze into a modernist cliffside house designed by architect Paolo Soleri, an Italian-born American transplant who pioneered an ecological vision of architecture that in many ways represents the possible fulfillment of Antonioni’s own search for spiritual harmony between nature and the exponential human progress of modernity. But that possibility is literally dynamited in a vision Daria has of the home abruptly blown to smithereens, the destruction replayed in slo-mo to the crashing squeals of early Pink Floyd, itself a collapse of psychedelic rock’s utopian ideals into acid-casualty freak-out. Hoping to find in America what he could not in either Italy nor Mod England, Antonioni instead sees a final, Boschian vision of obliteration to consume the false promise of the 20th century.

The slowly waning energy and sudden rapture of “Zabriskie Point” is mirrored in Monte Hellman’s existentialist road movie, “Two-Lane Blacktop.” Hellman’s film strips everything from the characters to their vehicle down to its essence: James Taylor and Dennis Wilson play amateur racers identified only as “The Driver” and “The Mechanic,” who crisscross the nation’s highways in a car they’ve equally shorn of every unnecessary accoutrement and aesthetic marker that impedes pure, functional speed. Accompanied by a “Girl” (Laurie Bird) hitchhiking to nowhere, the pair drift from race to race, winning just enough money to keep them in greasy spoon meals and gasoline.

Eventually, the group falls into an ambitious cross-country race challenged by G.T.O. (Warren Oates). The Driver and Mechanic see right through the man’s clear bluster and lack of actual racing know-how, but they form a strange bond with the man, becoming less competitors than loose companions. Perhaps the recognize their own directionless wanderlust in G.T.O., whose age and weariness breaks the film of a narrow commentary on disenchanted Baby Boomers and into a larger portrait of American malaise. “The thing is, you gotta keep moving,” G.T.O. tells one of many hitchhikers he picks up throughout the film and regales with a different life story, summarizing the shark-like instinct for constant motion that compels him as much as the three younger leads.

The closest thing that G.T.O. has to a fixed identity is the car he’s taken as a namesake, a subtle hint at the growing retreat into consumerism as a form of displaced self-actualization in the face of political disempowerment. He, more than the other characters, embodies the film’s lack of a conventional beginning, middle, or end. This narrative drift that comes to a head in a finale that mimics celluloid getting caught in a projector, the image slowing until finally a frame tears and catches fire — it’s a meta-textual ejection from a story that otherwise has no escape.

As bleak as these two films are, they at least end with a certain kind of nihilistic catharsis. No such release categorizes Bob Rafelson’s “Five Easy Pieces,” in which Robert Dupea (Jack Nicholson), the prodigal son of an abandoned upper-crust family to which he must return upon news of his father’s (Ralph Waite) failing health. Robert fled a life of classical music and parlor-room etiquette for blue-collar work and vulgar entertainment, but if he did so in search of some kind of authenticity, he found only the misery of wage labor.

Nicholson, hair prematurely thinning but possessed of a boyish spark he retained well into his elder years, is perhaps the ultimate symbol of a certain kind of developmental stasis among the Boomer generation. And while he would ultimately come to be seen as a rebellious figure on-screen, it’s here that one gets the clearest view of the underlying secret of so many of his most famous characters: Their refusal to conform or obey is ultimately an impotent gesture against forces larger than themselves.

We meet Robert already starting to fray from the everyday torments of traffic-slowed commutes and precarious job security, and he largely vents his frustrations on his girlfriend, Rayette Dipesto (Karen Black), whom he alternately insults and defends for her provincialism. Her desire to settle down triggers the same flight impulse that sent Robert away from his family, and only in a tender but one-sided scene where the man confesses his existential confusion to his stroke-addled father does he find a way to articulate his anxieties. The previous year, Rafelson’s production company scored a landmark counterculture hit with “Easy Rider,” which depicted hippie dropouts like western antiheroes eventually destroyed by a system that cannot tame them. “Five Easy Pieces” offers Robert no blaze of glory, only increasing isolation in a country that resembles Edward Hopper’s bleakest, loneliest paintings.

In Japan, theatrical audience loss to television resulted in the movie industry turning to exploitation cinema to entice crowds, leaving artier filmmakers few avenues for funding. One of the last bastions of radical cinema was the independent Art Theatre Guild, which produced and distributed two films in 1970 that captured Japan’s own retreat from possible change toward aesthetic and political conservatism.

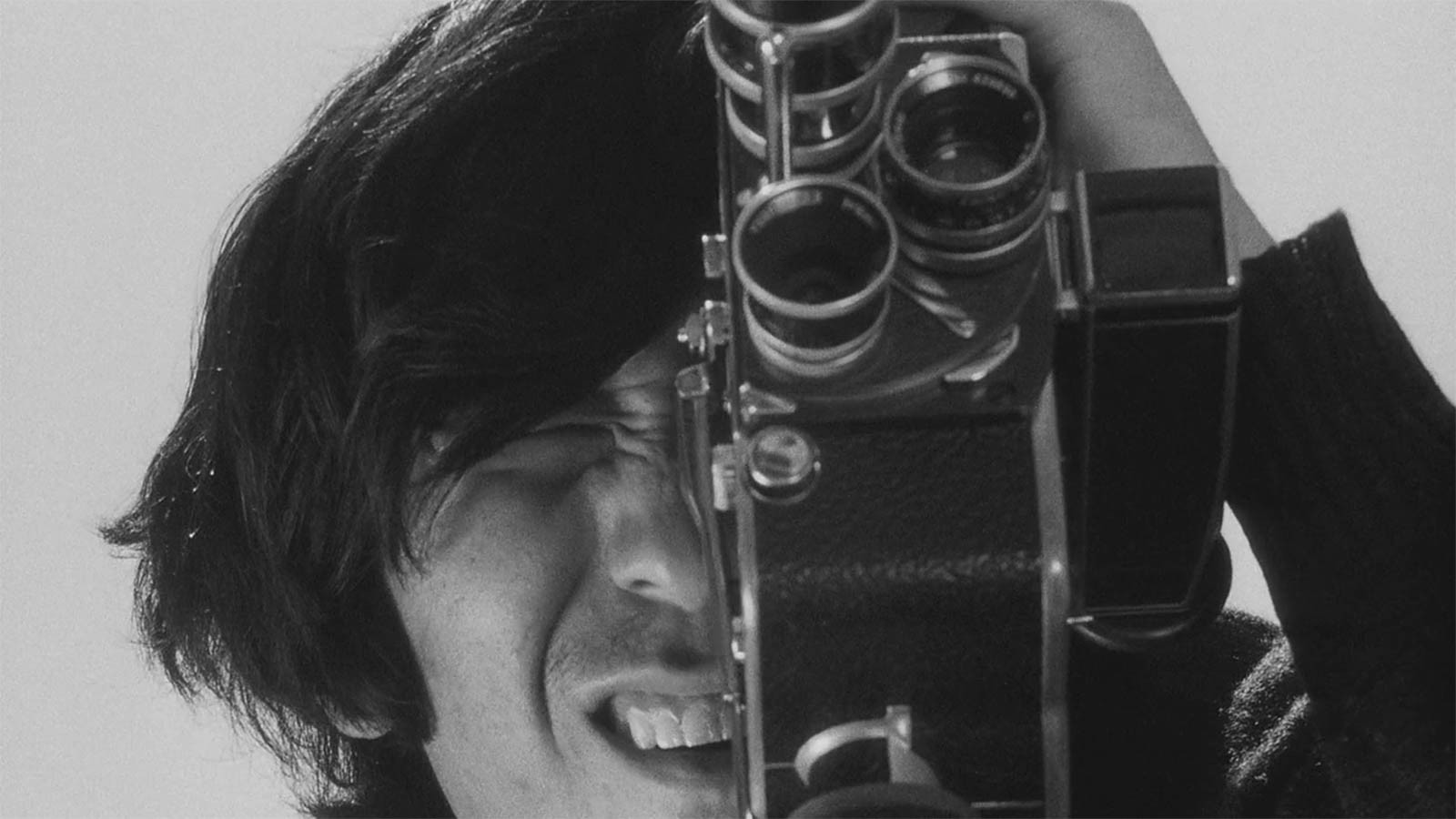

Nagisa Ōshima’s “The Man Who Left His Will on Film” begins with student filmmaker Motoki (Kazuo Goto) witnessing the suicide of rival colleague Endo (Kazuya Horikoshi), who leaves behind reels of film documenting his final days and possible clues about what prompted his death. Compared to the director’s more detached, Brechtian movies of the preceding decade (e.g. “Night and Fog in Japan,” “Double Suicide”), his 1970 feature is almost oppressively first-person, sinking ever deeper into Motoki’s paranoid need to find some kind of reason in Endo’s death even as more and more clues arise to suggest that the other student’s death may be nothing more than the protagonist’s hallucination.

Endo’s footage consists merely of poetic glimpses of city streets and landscapes, but its very lack of overt political intent convinces Motoki that there must be some hidden key to Endo’s demise. Perhaps he is right, but such abstruse, personal means of expression preclude wider understanding, and Ōshima suggests conflict within leftist movements not only over particular goals but the inability to balance collectivist struggle with the equal need for individual artistic vision.

Simlarly to Ōshima’s film, ATG stalwart Yoshishige Yoshida’s “Heroic Purgatory” also captures the self-defeating infighting among radical groups, though if anything Yoshida uses even more experimental techniques than his peer. His allegorical story concerns atomic engineer Shoda (Kaizo Kamoda), who returns home one day to discover his wife has taken in a teenage girl she claims to be his daughter.

“Heroic Purgatory” uses off-kilter camera compositions and fragmentary editing to establish a slippery relationship between reality and fantasy along with present and past. Shoda’s possible daughter behaves in ways both desperately longing and ruinously malevolent, and her antics come to symbolize the irreconcilable urges of political activists wishing to grow a collective political vision while succumbing to internal violence driven by individual ego.

Arguably the country most culturally obsessed with the failure of an international left was France, where the May 1968 demonstrations and eventual downfall have inspired artistic analysis well into the 21st century. Two of the most immediate responses came from the more outré figures of the French New Wave. Jacques Rivette’s mammoth 12-hour “Out 1” plays as a distended paranoid thriller, replacing the taut sensory overload of Alan J. Pakula with an almost comical lack of outward incident.

Slowly, though, strange details accumulate. A character introduced as deaf and non-verbal reveals that he can hear and speak. Characters disappear abruptly, and the ensemble is so large it’s easy not to realize it for some time. Gradually, a sense of unease arises, but it’s difficult to articulate what causes and whether clues to a larger conspiracy are real or just disconnected things ascribed meaning by those seeking to find some overriding logic in a world that feels increasingly unmoored and random.

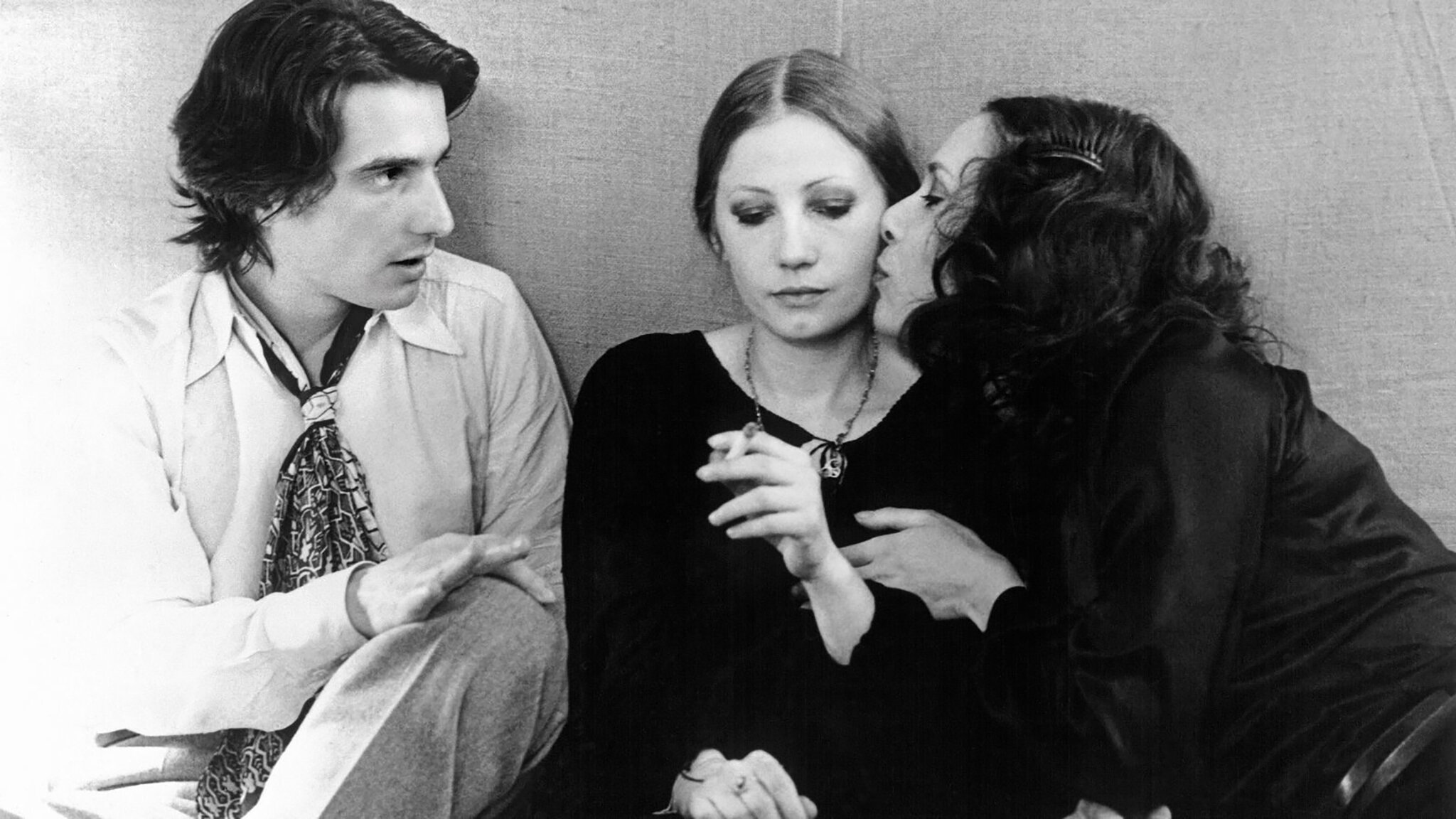

The ultimate postmortem, of both May ‘68 and the wider failure of the ‘60s left movement, can be found in Jean Eustache’s starkly directed, talky 1973 feature “The Mother and the Whore,” which uses the benefit of slight hindsight to make clearer observations of the aftershocks of political defeat. In the character of Alexandre (Jean-Pierre Léaud), a dejected radical turned arch-conservative, Eustache perceptively observes how erstwhile opponents of conservatism can become some of its most zealous converts.

It is Alexandre’s poisonously revanchist worldview that gives the film its title, referring as it does to the simplistic manner in which he perceives his exasperated lovers Marie (Bernadette Lafont) and Veronika (Françoise Lebrun). Despite his sexual relationship with both women, the young man looks from a modern vantage point like an eerie precursor to today’s incels and manosphere misogynists, compensating for his own feeling of powerlessness against the system by reasserting retrograde gender hierarchy to feel some sense of control.

And yet, if Alexandre presents a particularly dire warning of the side-effects of social surrender, “The Mother and the Whore” provides more hope than other such character studies in the way that Marie and Veronika slowly push the boundaries of the pigeonholes in which the man seeks to confine them. Discontent to allow this unimpressive man to roll back the seeds of women’s progress over the last decade to force them back into the reductive roles of the film’s title, the women find strength in forging their own relationship as a bulwark against Alexandre’s controlling nature. While the envisioned leaps and bounds of progress of the ‘60s may have been halted, the steps made cannot be fully reversed. Even so, it’s hard not to notice that the collective movements of the previous decade are now replaced by far smaller acts of individual resistance, a daily grind of trench warfare just to hold position in stalemated territory.

IndieWire’s ‘70s Week is presented by Bleecker Street’s “RELAY.” Riz Ahmed plays a world class “fixer” who specializes in brokering lucrative payoffs between corrupt corporations and the individuals who threaten their ruin. IndieWire calls “RELAY” “sharp, fun, and smartly entertaining from its first scene to its final twist, ‘RELAY’ is a modern paranoid thriller that harkens back to the genre’s ’70s heyday.” From director David Mackenzie (“Hell or High Water”) and also starring Lily James, in theaters August 22.